As Black History Month draws to a close and we are about to embark on Women’s History Month, one pioneering composer neatly straddles the intersection: Florence Price (1887-1953). Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, Price struggled her entire life with the effects of segregation, misogyny, and racism, despite her undeniable talents as a musician and composer. In a letter to famed conductor Serge Koussevitzky (who, incidentally, ignored her attempt to send him scores), she wrote,

To begin with I have two handicaps – those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins. Knowing the worst, then, would you be good enough to hold in check the possible inclination to regard a woman’s composition as long on emotionalism but short on virility and thought content; – until you shall have examined some of my work? As to the handicap of race, may I relieve you by saying that I neither expect nor ask any concession on that score. I should like to be judged on merit alone.

Despite the grip segregation had on the United States, Price’s early years in Little Rock were comfortable. At the time, Little Rock was reasonably integrated, and a strong, Black middle class flourished. Her father’s occupation as a dentist allowed for a lavish home, music lessons, and a well-rounded education. Her family operated in exclusive circles, with such notable figures as statesman Frederick Douglass visiting her home. By age four, Price was already presenting piano recitals after studying music with her mother, and her first composition was published at age 11. She finished first in her high school class at the tender age of 14. Both she and another prominent African-American composer, William Grant Still, grew up together.

Despite the grip segregation had on the United States, Price’s early years in Little Rock were comfortable. At the time, Little Rock was reasonably integrated, and a strong, Black middle class flourished. Her father’s occupation as a dentist allowed for a lavish home, music lessons, and a well-rounded education. Her family operated in exclusive circles, with such notable figures as statesman Frederick Douglass visiting her home. By age four, Price was already presenting piano recitals after studying music with her mother, and her first composition was published at age 11. She finished first in her high school class at the tender age of 14. Both she and another prominent African-American composer, William Grant Still, grew up together.

Unfortunately, Jim Crow laws eventually made their way to Little Rock, greatly affecting her father’s ability to work and restricting Price’s aspirations as a musician. She decided to move north to attend the New England Conservatory (NEC), one of only a few conservatories at the time that accepted both women and African-Americans. Even in Boston, she claimed to be Mexican on the advice of her mother to avoid blatant discrimination. Price was clearly a standout student at NEC, the only one in her class to receive a double degree (in piano teaching and organ performance) in only three years. She also continued her compositional studies while there.

Upon returning home, she soon realized that the segregation of the south severely limited her aspirations, and moved to Chicago, where she completed additional composition studies at several institutions, including the Chicago Musical College, now Roosevelt University. She was a critical participation in Chicago’s Black Renaissance, creating great works of art alongside other artists in a variety of fields.

Price’s Works

Price’s output is quite large, and includes four symphonies, two violin concertos, a piano concerto, two string quartets and piano quintets, and numerous vocal, piano, and organ works. Much of her output was nearly lost, found only in 2009 in a run-down house she had used as a summer home. Nearly lost were both her violin concertos and her Fourth Symphony, among other works.

CMPI Violin Fellow Aiden Daniels calls her work, “folk-inspired but classically trained.” Her writing is unique in its combination of traditional African-American spirituals and folk music with modernism, with a special talent for compelling orchestration, lyricism, and richness. Some of her works have titles referencing the Black experience in the South, while others use the melody and rhythms of spirituals and other traditional pieces. Her writing is accessible through its thoroughly American use of melody, but with greater harmonic exploration, rhythmic adventurousness, and a progressively more modern aesthetic.

Of particular note is her Symphony 1, which was the first place winner of Wanamaker Foundation Awards in 1932. The then all-white and all-male Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered it in 1933, the first time a major orchestra performed an orchestral work by an African-American woman. Many of its movements contain lavish orchestrations of reworked folk melodies, and the third movement is notable for its lively syncopated Juba dance, a style of stomping and clapping dance performed by slaves.

Florence Price is a composer whose works surely need to be played more often. Please enjoy this virtual performance of the final movement of her First Symphony by Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra, which includes a number of current and former CMPI students.

Images

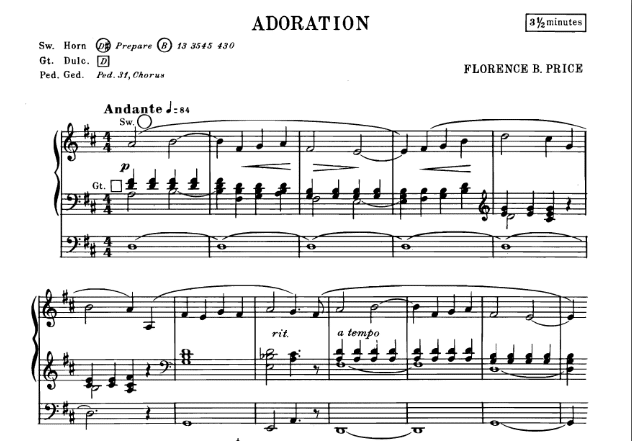

Florence Price’s Adoration for Organ

Headshot of Florence Price