When string players look at almost any audition list, they will see a commonality: a required movement or two of unaccompanied Bach. Violinists are typically asked to play from Bach’s 6 Sonatas and Partitas, while violists, cellists, and sometimes even bass players perform Bach’s 6 Suites. Beginning in middle or high school, students typically consume a steady diet of these incredible Bach works.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was a composer from the Baroque period. His Violin Sonatas and Partitas were completed in 1720, while the Cello Suites were composed from 1717 until 1723. Both the Cello Suites and the Violin Partitas are collections of primarily dance movements, while the Violin Sonatas are four-movement works. Both collections are hailed as some of the most beautiful of the repertoire, in addition to being pedagogically important for musicians.

The 6 Suites and the 6 Sonatas and Partitas are written in a variety of keys, as listed in the table below. Interestingly, the final Cello Suite was originally composed for an unknown five-string instrument, perhaps the violoncello piccolo, viola pomposa, or violoncello da spalla (shoulder cello), and typically requires some accommodations to be performed on a modern four-string cello or viola. The fifth Cello Suite also originally included scordatura or mistuning, which in this case means the highest string is tuned down to G, though many modern players just use regular tuning.

Violin Sonatas and Partitas

Violin Sonata No. 1 – G minor

Violin Partita No. 1 – B minor

Violin Sonata No. 2 – A minor

Violin Partita No. 2 – D minor

Violin Sonata No. 3 – C major

Violin Partita No. 3 – E major

Cello Suites

Cello Suite No. 1 – G major

Cello Suite No. 2 – D minor

Cello Suite No. 3 – C major

Cello Suite No. 4 – Eb major

Cello Suite No. 5 – C minor

Cello Suite No. 6 – D major

Baroque Forms

According to violin fellow Noah Briones, “An important technique that I focus on when playing unaccompanied Bach is the rhythm and style of the piece, based on the intention of Bach. This means I always keep in mind whether it is a dance, a mournful piece, a showpiece, or an introduction, as just a few examples.” There are four primary types of pieces in unaccompanied Bach: slow, improvisatory movements, fugues, dance movements, and more standard sonata movements.The Violin Sonatas all begin with a slow, improvisatory movement with written out ornamentation, including trills and runs. Each is followed by a very challenging fugue, a type of contrapuntal musical composition that begins with a theme or subject that is then repeated in the other voices successively, adding layers on top of each other. In these unaccompanied fugues, the performer faces the challenge of playing all of the various voices on a single instrument, primarily using double stops. Finally, each sonata concludes with a pair of movements, one moderately slow and the other fast tempo.

Violin Sonata Form

- Slow improvisatory movement

- Fugue

- Moderate tempo movement

- Fast movement

Cello Suite Form

- Prelude

- Allemande

- Courante

- Sarabande

- Pair of Galanteries: Bourees, Gavottes, or Minuets

- Gigue

In contrast, the Violin Partitas and Cello Suites are primarily composed of dance movements. In some cases, such as in Partita No. 3 and all of the Cello Suites, the collection opens with a prelude. Most of these have a somewhat improvisatory or rubato feeling. Of special note is Cello Suite No. 5, which begins with a prelude consisting of an improvisatory opening with written out ornamentation followed by a single line fugue, mirroring the opening of the Violin Sonatas. Two other Violin Partitas also have special features. Partita No. 1 includes a “double” version of each movement, in which the player plays twice as many notes using ornamentation and arpeggiation. Partita No. 2 ends with the well-known full-length Chaconne — as long as the entire rest of the Partita put together — which is widely regarded as one of the grandest and most transcendent works in the repertoire. It is a series of variations over a repeated bass line.The remaining movements of the suites and partitas are straightforward dances, both fast and slow, in duple and triple meters. While the Cello Suites have a fixed formal pattern, the Violin Partitas vary in both the number of movements and the type of dances chosen.

While these dance movements were not intended to actually be danced, they still retain the stylized elements of Baroque dance forms. As such, they should be played at tempos that are moderate enough to be danced to, and should preserve the characteristic style of the dance, such as appropriately emphasized beats or the use of dotted rhythms. An overview of the types of dance movements can be found by selecting the name of each dance below.

- Moderately Slow Tempo

- Duple Rhythmic Feel

- Often has a dotted or tied note on the downbeat

- Fast Tempo

- Triple Rhythmic Feel

- More virtuosic

- Slow Tempo

- Triple Rhythmic Feel

- Often emphasizes beat 2

- Slow Tempo

- Triple Rhythmic Feel

- Stately, with heavy pickup

- Moderate Tempo

- Duple Rhythmic Feel

- Always has a pickup

- Moderate Tempo

- Duple Rhythmic Feel

- Always starts in the middle of the bar

- Moderate Tempo

- Triple Rhythmic Feel

- Always starts on the downbeat

- Fast Tempo

- Triple Rhythmic Feel

- Fast, sometimes with dotted rhythms

Baroque Style and Articulation

Unaccompanied Bach must be played in a Baroque style. Of course, there are many different levels of what is called Historically Informed Performance. Some players may just use the articulations and bowings of the Baroque period, while others may use a Baroque bow or even a Baroque instrument. Viola fellow Na’ilah Shahid says, “I think the hardest part of solo Bach is shaping how you want it to sound. Often people consider what music was and sounded like in this time period while shaping and others just do what they feel it should sound like. In my opinion, there’s really no wrong answer, though I prefer a mix between the two.”

As violin fellow Dean Barrow states, “Compared to other classical pieces, the music of solo Bach has a different style. To try and fit the style, I spend the majority of my time working on articulation. The bow has to be lighter on the string instead of aggressively pressing the string.” Violin fellow Neal Eisfeldt reflects similarly. “There are several important techniques to get a clean sound in Bach. These include a combination of correct intonation, the right bow speed, and the right phrasing. One of the most important techniques I learnt is that Bach needs a brisk, staccato style of bowing and has no place for one to suddenly play a legato style bowing. Staccato bowing and ending each phrase with a subtle vibrato makes it that much more melodious and special.”

Double, Triple, and Quadruple Stops

Double, triple, and even quadruple stops are omnipresent in these works, especially in the violin repertoire. In some cases the double stops are more ornamental in nature, giving extra emphasis to an opening or cadence. But in other cases, such as in the fugues and Chaconne, they represent separate melodies that the player must bring out. Note that in today’s performance practice, all double stops should be played from the bottom to the top, from lowest note to highest note. One recommendation to learn how to play these double stops is to experiment with an inexpensive Baroque bow, now widely available for around $100, which allows the player to more easily create elegant triple and quadruple stops.

Harmony, Melody, and Voicing

Cello fellow Jan Vargas-Nedvetsky believes that, “An important thing to be aware of in Bach is the harmonic structure. Bach normally wrote for organ or other keyboard instruments, so when we look at his solo music we find many different voices played by just one line. While it is important to be aware of these harmonies, it is more important to understand how they fit into the music. We must remember that, even if we understand the structure of the music intellectually we must also be able to convey it so others can understand it as well.”

For example, in the Prelude from Partita No. 3, Bach alternates repeated pitches with an ascending melodic line, giving the effect of one player playing a melody, while another plays a sustained pitch.

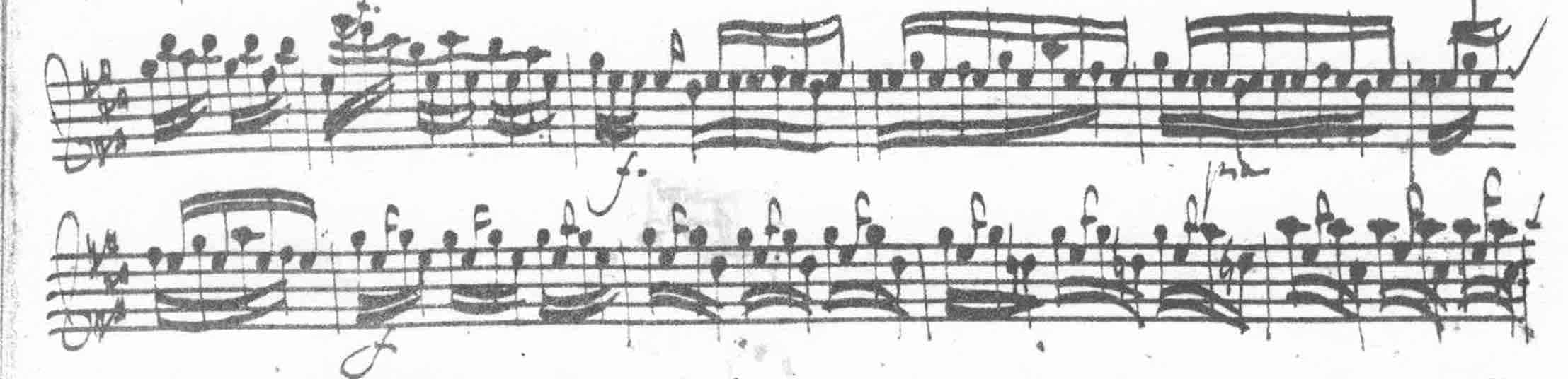

In other movements, double stops are used to create multiple voices. In many of these movements, identifying and bringing out the bass line from the texture is critically important, as shown in the example from Sonata No. 2 below.

According to violin fellow Sameer Agrawal, “Unlike most other pieces, you have to play both melody and harmony at the same time when playing unaccompanied Bach.” For him, this means a special focus on intonation. “Because you are playing by yourself, you have the ability to use expressive intonation, but also at the same time you have to make sure notes are very in tune with each other and open strings. You have to learn which notes to play completely in tune and which notes to adjust the intonation so both the melody and harmony sound in tune.”

Bowing and Dynamics

Bowings and slurs are very inconsistent in these works, due to a variety of factors from copying problems to imprecise markings and bowings that just do not work out. There are many different editions available that reconcile the bowings in numerous ways; however, many older ones are heavy-handed and add numerous slurs that were unintended. Players should always consult the original copies, which are available for free on IMSLP, or use an edition in which the added bowings and slurs are clearly differentiated from the original markings. Click here for the manuscript of the Violin Sonatas and Partitas or here for the earliest copy of the Cello Suites. It is impossible to play the original slurs and bowings exactly, as they always require some degree of bowing correction, but players should strive toward minimal additions of slurs. With the exception of a few echos, Bach rarely included dynamics in these works. The player must interpret both where to place pianos and fortes, and must also determine where crescendos and decrescendos are appropriate.

Ornamentation (Written and Unwritten)

Some movements, especially the first movements of the Violin Sonatas or the fifth Cello Suite Prelude, can be thought of as having written out ornaments. They include a slow melodic line that is embellished with runs, arpeggios, and double stops. Bach also occasionally includes trills in places of importance, like cadences. However, it is also a common practice to add ornamentation to these works. Some players only add extra trills, which may even be printed in some editions. Other players choose to add significant ornamentation — runs, turns, trills, and arpeggios — to certain movements. It is common practice in movements with repeats to play the first time through in a relatively plain manner, while adding numerous ornaments — planned or improvised — when playing the repeat.

The Difficulty of Playing Bach

If you have ever heard Yo-Yo Ma play the Cello Suites, you know how beautiful and elegant they sound. But getting Bach to sound this way is no easy feat. As violinist Dean Barrow says, “To a listener, the pieces sound quite simple and elegant; however, to play solo Bach well, there are many complex techniques that one has to play. For example, there will be passages where the melody is quite nice; however, it consists of tricky double stops and chords that can be uncomfortable for the player.”

For cellist Jan Vargas-Nedvetsky, “Playing solo Bach is a test of all of the abilities of a musician. Even though it may seem easy when we look at the notes on the page, we must both understand the structure and style while being able to play it accurately and artistically.” Herein lies the true art of these masterpieces: the submission of technique to the elegance of the music.

Sample Performances by Fellows

Images

Bach, Sonata No. 3, Prelude, original manuscript

Analyzed version of Bach, Sonata No. 2, Grave, by Susan Agrawal